Ukrainian is a language of the East Slavic subgroup of the Slavic languages. It is the official state language of Ukraine. Written Ukrainian uses a variant of the Cyrillic alphabet.

The Ukrainian language traces its origins to the Old East Slavic of the early medieval state of Kievan Rus'. Ukrainian is a lineal descendant of the colloquial language used in Kievan Rus' (10th–13th century). From 1804 till the Russian Revolution Ukrainian was banned from schools in the Russian Empire where Ukraine was a part of at the time. It has always maintained a sufficient base among the Ukrainian people (especially in Western Ukraine where the language was never banned) in its folklore songs, itinerant musicians, and prominent authors.

Theories concerning the Ukrainian language's development

The first theory of the origin of Ukrainian language was suggested in Imperial Russia in the middle of the 18th century by Mikhail Lomonosov. This theory posits the existence of a common language spoken by all East Slavic people in the time of the Rus'. According to Lomonosov, the differences that subsequently developed between Great Russian and Ukrainian (he referred to as Little Russian) could be explained by the influence of the Polish and Turkic languages on Ukrainian and the influence of Uralic languages on Russian from the 13th to the 17th centuries.

The "Polonization" theory was criticized as early as the first half of the 19th century by Mykhailo Maxymovych. The most distinctive features of the Ukrainian language are present neither in Russian nor in Polish. Ukrainian and Polish do share many common or similar words, but so do all Slavic languages, since many words originated in the Proto-Slavic language, the common ancestor of all modern Slavic languages. A much smaller part of their common vocabulary can be attributed to the later interaction of the two languages. The "Polonization" theory has not been seriously regarded by the academic community since the beginning of the 20th century, although it is still sometimes cited.

Another point of view developed during the 19th and 20th centuries by linguists of Imperial Russia and the Soviet Union. Like Lomonosov, they assumed the existence of a common language spoken by East Slavs in the past. But unlike Lomonosov's hypothesis, this theory does not view "Polonization" or any other external influence as the main driving force that led to the formation of three different languages: Russian, Ukrainian and Belarusian from the common Old East Slavic language. This general point of view is the most accepted amongst academics world-wide, particularly outside Ukraine. The supporters of this theory disagree, however, about the time when the different languages were formed.

Soviet scholars set the divergence between Ukrainian and Russian only at later time periods (14th through 16th centuries). According to this view, Old East Slavic diverged into Belarusian and Ukrainian to the west (collectively, the Ruthenian language of the 15th to 18th centuries), and Old Russian to the north-east, after the political boundaries of Kievan Rus' were redrawn in the 14th century. During the time of the incorporation of Ruthenia (Ukraine and Belarus) into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Ukrainian and Belarusian diverged into identifiably separate languages.

Some scholars see a divergence between the language of Galicia-Volhynia and the language of Novgorod-Suzdal by the 12th century, assuming that before the 12th century, the two languages were practically indistinguishable. This point of view is, however, at variance with some historical data. In fact, several East Slavic tribes, such as Polans, Drevlyans, Severians, Dulebes (that later likely became Volhynians and Buzhans), White Croats, Tiverians and Ulichs lived on the territory of today's Ukraine long before the 12th century. Notably, some Ukrainian features were recognizable in the southern dialects of Old East Slavic as far back as the language can be documented.

Some researchers, while admitting the differences between the dialects spoken by East Slavic tribes in the 10th and 11th centuries, still consider them as "regional manifestations of a common language" (see, for instance, the article by Vasyl Nimchuk). In contrast, Ahatanhel Krymsky and Alexei Shakhmatov assumed the existence of the common spoken language of Eastern Slavs only in prehistoric times. According to their point of view, the diversification of the Old East Slavic language took place in the 8th or early 9th century.

Ukrainian linguist Stepan Smal-Stotsky went even further, denying the existence of a common Old East Slavic language at any time in the past. Similar points of view were shared by Yevhen Tymchenko, Vsevolod Hantsov, Olena Kurylo, Ivan Ohienko and others. According to this theory, the dialects of East Slavic tribes evolved gradually from the common Proto-Slavic language without any intermediate stages during the 6th through 9th centuries. The Ukrainian language was formed by convergence of tribal dialects, mostly due to an intensive migration of the population within the territory of today's Ukraine in later historical periods. This point of view was also confirmed by Yuri Shevelov's phonological studies and, although it is gaining a number of supporters among Ukrainian academics, it is not seriously regarded outside Ukraine.

Outside Ukraine, however, such nationalist-based theories that distance Ukrainian from East Slavic have found few followers among international scholars and most academics continue to place Ukrainian firmly within the East Slavic group, descended from Proto-East Slavic, with close ties to Belarusian and Russian.

Origins and developments during medieval times

Ukrainian traces its roots through the mid-14th century Ruthenian language, a chancellery language of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, back to the early written evidences of 10th century Rus'. Until the end of the 18th century, the written language used in Ukraine was quite different from the spoken, which is one of the key difficulties in tracing the origin of the Ukrainian language more precisely. The language was constantly persecuted as the territory of Ukraine was divided mainly between Poland and Russia, and as a result there is little direct data on the origin of the Ukrainian language. Scholars rely on indirect methods: analysis of typical mistakes in old manuscripts, comparison of linguistic data with historical, anthropological, archaeological ones, etc. Several theories of the origin of Ukrainian language exist. Some early theories have been proven wrong by modern linguistics (yet continue to be cited), while others are still being discussed in the academic community.

It is believed that up to the 14th century, ancestors of the modern Ukrainians spoke dialects of the language known collectively as Old East Slavic (today known as Ruthenian language), also spoken by other East Slavs of Kievan Rus. That mainly spoken tongue was used alongside Old Church Slavonic, the literary language of all Slavs. The earliest written record of the language is an amphora found at Gnezdovo and tentatively dated to the mid-10th century. Until the 15th century, Gnezdovo was a part of the independent Smolensk principality.

It is known that between 9th and 13th century, many areas of modern Ukraine, Belarus and parts of Russia were united in a common entity now referred to as Rus'. Surviving documents from the Kievan Rus' period are written in either Old East Slavic or Old Church Slavonic language or their mixture. Different earldoms of Rus' had different dialects of Old East Slavic. These languages are considerably different from both modern Ukrainian and Russian, but similar enough that a modern educated Ukrainian or Russian reader can understand 11th-century texts reasonably well.

During the 13th century, when German settlers were invited to Ukraine by the princes of Galicia-Vollhynia, German words began to appear in the language spoken in Ukraine. Their influence would continue under Poland not only through German colonists but also through the Yiddish-speaking Jews. Often such words involve trade or handicrafts. Examples of words of German or Yiddish origin spoken in Ukraine include dakh (roof), rura (pipe), rynok (market), kushnir (furrier), and majster (master or craftsman).

Developments under Poland and Lithuania

In the 13th century, eastern parts of Rus' (including Moscow) came under Tatar yoke until their unification under the Tsardom of Muscovy, whereas the south-western areas (including Kiev) were incorporated into the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. For the following four centuries, the language of the two regions evolved in relative isolation from each other. Direct written evidence of the existence of the Ukrainian language dates to the late 16th century. By the 16th century, a peculiar official language was formed: a mixture of Old Church Slavonic, Ruthenian and Polish with the influence of the last of these three gradually increasing. Documents soon took on many Polish characteristics superimposed on Ruthenian phonetics. Polish rule and education also involved significant exposure to the Latin language. Much of the influence of Poland on the development of the Ukrainian language has been attributed to this period and is reflected in multiple words and constructions used in everyday Ukrainian speech that were taken from Polish or Latin. Examples of Polish words adopted from this period include zavzhdy (always; taken from old Polish word zawżdy) and obitsiaty (to promise; taken from Polish obiecać) and from Latin raptom (suddenly) and meta (aim or goal).

Significant contact with Tatars and Turks resulted in many Turkic words, particularly those involving military matters and steppe industry, being adopted into the Ukrainian language. Examples include torba (bag) and tyutyun (tobacco).

By the mid-17th century, the linguistic divergence between the Ukrainian and Russian languages was so acute that there was a need for translators during negotiations for the Treaty of Pereyaslav, between Bohdan Khmelnytsky, head of the Zaporozhian Host, and the Russian state.

History of the Ukrainian spoken language's usage

Rus' and Galicia-Volhynia

During the Khazar period, the territory of Ukraine, settled at that time by Iranian (post-Scythian), Turkic (post-Hunnic, proto-Bulgarian), and Uralic (proto-Hungarian) tribes, was progressively Slavicized by several waves of migration from the Slavic north. Finally, the Varangian ruler of Novgorod, called Oleg, seized Kiev (Kyiv) and established the political entity of Rus'. Some theorists see an early Ukrainian stage in language development here; others term this era Old East Slavic or Old Ruthenian/Rus'ian. Russian theorists tend to amalgamate Rus' to the modern nation of Russia, and call this linguistic era Old Russian. Some hold that linguistic unity over Rus' was not present, but tribal diversity in language was.

The era of Rus' is the subject of some linguistic controversy, as the language of much of the literature was purely or heavily Old Slavonic. At the same time, most legal documents throughout Rus' were written in a purely Old East Slavic language (supposed to be based on the Kiev dialect of that epoch). Scholarly controversies over earlier development aside, literary records from Rus' testify to substantial divergence between Russian and Ruthenian/Rusyn forms of the Ukrainian language as early as the era of Rus'. One vehicle of this divergence (or widening divergence) was the large scale appropriation of the Old Slavonic language in the northern reaches of Rus' and of the Polish language at the territory of modern Ukraine. As evidenced by the contemporary chronicles, the ruling princes of Galich (modern Halych) and Kiev called themselves "People of Rus'" (with the exact Cyrillic spelling of the adjective from of Rus varying among sources), which contrasts sharply with the lack of ethnic self-appellation for the area until the mid-19th century.

One prominent example of this north-south divergence in Rus' from around 1200, was the epic, The Tale of Igor's Campaign. Like other examples of Old Rus' literature (for example, Byliny, the Primary Chronicle), which survived only in Northern Russia (Upper Volga belt) and was probably created there. It shows dialectal features characteristic of Severian dialect with the exception of two words which were wrongly interpreted by early 19th century German scholars as Polish loan words.

Under Lithuania/Poland, Muscovy/Russia, and Austro-Hungary

After the fall of Galicia–Volhynia, Ukrainians mainly fell under the rule of Lithuania, then Poland. Local autonomy of both rule and language was a marked feature of Lithuanian rule. In the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Old Slavic became the language of the chancellery and gradually evolved into the Ruthenian language. Polish rule, which came mainly later, was accompanied by a more assimilationist policy. By the 1569 Union of Lublin that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, a significant part of Ukrainian territory was moved from Lithuanian rule to Polish administration, resulting in cultural Polonization and visible attempts to colonize Ukraine by the Polish nobility. Many Ukrainian nobles learned the Polish language and adopted Catholicism during that period. Lower classes were less affected because literacy was common only in the upper class and clergy. The latter were also under significant Polish pressure after the Union with the Catholic Church. Most of the educational system was gradually Polonized. In Ruthenia, the language of administrative documents gradually shifted towards Polish.

The Polish language has had heavy influences on Ukrainian (and on Belarusian). As the Ukrainian language developed further, some borrowings from Tatar and Turkish occurred. Ukrainian culture and language flourished in the sixteenth and first half of the 17th century, when Ukraine was part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Among many schools established in that time, the Kiev-Mogila Collegium (the predecessor of modern Kyiv-Mohyla Academy), founded by the Orthodox Metropolitan Peter Mogila (Petro Mohyla), was the most important. At that time languages were associated more with religions: Catholics spoke Polish language, Orthodox spoke Rusyn language.

After the Treaty of Pereyaslav, Ukrainian high culture was sent into a long period of steady decline. In the aftermath, the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was taken over by the Russian Empire and closed down later in 19th century. Most of the remaining Ukrainian schools also switched to Polish or Russian, in the territories controlled by these respective countries, which was followed by a new wave of Polonization and Russification of the native nobility. Gradually the official language of Ukrainian provinces under Poland was changed to Polish, while the upper classes in the Russian part of Ukraine used Russian widely.

There was little sense of a Ukrainian nationality in the modern sense. East Slavs called themselves Rus’ki ('Russian' pl. adj.) in the east and Rusyny ('Ruthenians' n.) in the west, speaking Rus’ka mova, or simply identified themselves as Orthodox (the latter being particularly important under the rule of Catholic Poland). A part of Ukraine under the Russian Empire was called Russia Minor (Malorossija) by the Russian establishment, where the inhabitants were considered to speak the “Little Russian language” (malorossijskij jazyk) or “Southern Russian dialect” (južno-russkie narečie) of the Russian literary language.

During the 19th century, a revival of Ukrainian self-identity manifested itself in the literary classes of both Russian-Empire Dnieper Ukraine and Austrian Galicia. The Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius in Kiev applied an old word for the Cossack motherland, Ukrajina, as a self-appellation for the nation of Ukrainians, and Ukrajins’ka mova for the language. Many writers published works in the Romantic tradition of Europe demonstrating that Ukrainian was not merely a language of the village, but suitable for literary pursuits.

However, in the Russian Empire expressions of Ukrainian culture and especially language were repeatedly persecuted, for fear that a self-aware Ukrainian nation would threaten the unity of the Empire. In 1804 Ukrainian as a subject and as language of instruction was banned from schools. In 1811 by the Order of the Russian government the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy was closed. The Academy that had been open since 1632 and was the first university in the eastern Europe, was now proclaimed to be outlaw. In 1847 the Brotherhood of Sts Cyril and Methodius was terminated. The same year Taras Shevchenko was arrested and exiled for ten years, and banned for political reasons from writing and painting. In 1862 Pavlo Chubynsky was exiled for seven years out of Ukraine to Arkhangelsk. The Ukrainian magazine Osnova was discontinued. In 1863, the tsarist interior minister Pyotr Valuyev proclaimed in his decree that "there never has been, is not, and never can be a separate Little Russian language". A following ban on Ukrainian books led to Alexander II's secret Ems Ukaz, which prohibited publication and importation of most Ukrainian-language books, public performances and lectures, and even the printing of Ukrainian texts accompanying musical scores. A period of leniency after 1905 was followed by another strict ban in 1914, which also affected Russian-occupied Galicia.

For much of the 19th century the Austrian authorities demonstrated some preference for Polish culture, but the Ukrainians were relatively free to partake in their own cultural pursuits in Halychyna and Bukovyna, where Ukrainian was widely used in education and in official documents. The suppression by Russia retarded the literary development of the Ukrainian language in Dnipro Ukraine, but there was a constant exchange with Halychyna, and many works were published under Austria and smuggled to the east.

By the time of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the collapse of Austro-Hungary in 1918, the former 'Ruthenians' or 'Little Russians' were ready to openly develop a body of national literature, to institute a Ukrainian-language educational system, and to form an independent state, named Ukraine (the Ukrainian People's Republic, shortly joined by the West Ukrainian People's Republic). During this brief independent statehood the statue and use of Ukrainian greatly improved.

Speakers in the Russian Empire

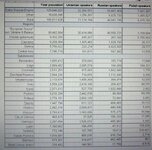

In the Russian Empire Census of 1897 the following picture emerged, with Ukrainian being the second most spoken language of the Russian Empire. According to the Imperial census's terminology, the Russian language (Russkij) was subdivided into Ukrainian (Malorusskij, 'Little Russian'), what we know as Russian today (Vjelikorusskij, 'Great Russian'), and Belarusian (Bjelorusskij, 'White Russian').

The following table shows the distribution of settlement by native language ("po rodnomu jazyku") in 1897, in Russian Empire governorates (guberniyas) which had more than 100,000 Ukrainian speakers.

Although in the rural regions of the Ukraine provinces, 80% of the inhabitants said that Ukrainian was their native language in the Census of 1897 (for which the results are given above), in the urban regions only 32.5% of the population claimed Ukrainian as their native language. For example, in Odessa, the largest city of Ukraine at this time, only 5.6% of the population said Ukrainian was their native language. Until the 1920s the urban population in Ukraine grew faster than the number of Ukrainian speakers. This implies that there was a (relative) decline in the use of Ukrainian language. For example, in Kiev, the number of people stating that Ukrainian was their native language declined from 30.3% in 1874 to 16.6% in 1917.

Тільки зареєстровані користувачі бачать весь контент у цьому розділі

)

)

может напомнить такую "мелочь" как МВ и МВ2?

может напомнить такую "мелочь" как МВ и МВ2?